Originalus straipsnis ČIA

In a provocative article published last weekend, Joe Hildebrand argued that “We are fast approaching a point where anyone who refuses whatever vaccine they are eligible for can no longer consider themselves a truly decent member of society.”

Australian health authorities, supporting Hildebrand’s bold claim, now try to achieve the goal of full vaccination by scaring and threatening people. For example, a dozen health officials signed a letter, published in The Australian last week in which they pleaded with people to get vaccinated, warning that the “only options” are being vaccinated or dying from a Covid infection.

The Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, speaking to the press last Thursday, foreshadowed that people who are unvaccinated “will face more restrictions”. This potentially means that the unvaccinated may no longer have unrestricted access to travel, or may not be allowed to attend football matches, concerts, and festivals. The Prime Minister believes that his comment describes a “common sense” approach — that those who pose a ‘greater health risk’ to others for not being vaccinated should not be allowed to enjoy the same level of rights and freedoms.

In this context, Associate Professor Ron Levy from the Australian National University, who specialises in constitutional law, opined that any constitutional challenge to restricting the unvaccinated would face an uphill battle in the courts. He said the High Court would likely be averse to preventing governments acting on public health matters. “There isn’t too much that can be done, constitutionally speaking,” he said.

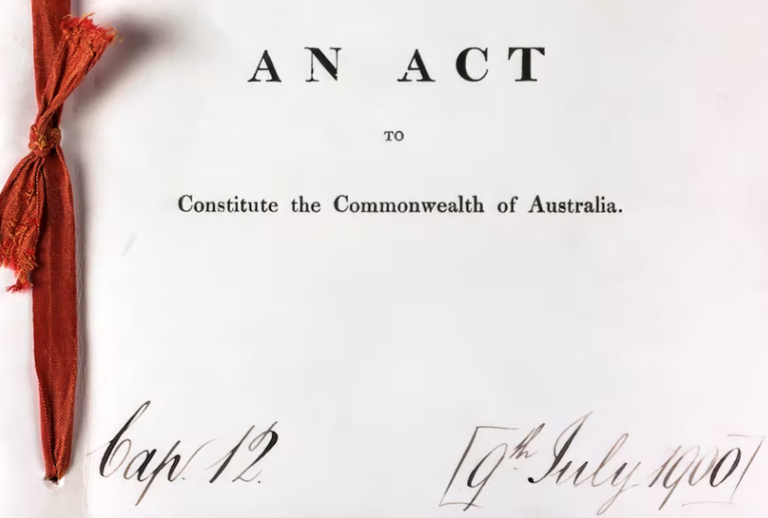

Although Levy’s assessment may be correct with regards to what the High Court might do, it is not necessarily the same as to what it should do if it were called upon to consider the constitutionality of mandatory vaccinations. Accordingly, any assessment of the constitutionality of vaccination directives should consider that the purpose of the Australian Constitution was to establish an institutional arrangement capable of restricting arbitrary power and ensuring limited government. The Australian governments should act within, and in conformity with, these legal-institutional limitations.

This classical liberal tradition of constitutionalism laid the basis for representative democratic government and the legal protection of citizens against the exercise of arbitrary political power. Under this tradition, to be under the rule of law presupposes the existence of rules and principles serving as an effective check on such political power.

A failure to effectively protect the constitutional framework would transform the Constitution into a less reliable document when it comes to restricting political power and ensuring the proper operation of constitutional government. In this context, Giovanni Sartori, an Italian political scientist, would properly describe such a constitution as no more than a “façade”. Specifically, this would be the case if the mechanisms for limiting the power of government appears to be considerably disregarded at least in their most essential features.

One of the most remarkable characteristics of the Australian Constitution is its express limitation on governmental powers. In drafting the Constitution, the framers sought to design an instrument of government intended to distribute and limit the powers of the state. This distribution of, and limitation upon, governmental powers was deliberately chosen because of the proper understanding that unrestrained power is always inimical to the achievement of human freedom and happiness.

Accordingly, the Constitution allocates the areas of legislative power to the Commonwealth primarily in sections 51 and 52, with these powers being variously exclusive or concurrent with the Australian states.

The Constitution was amended in a referendum in 1946 to include section 51(xxiiiA). This provision determines that the Commonwealth parliament, among others, can make laws with respect to: “the provision of … pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorize any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances.”

This provision allows for the granting of various services by the federal government but not to the extent of authorising any form of civil conscription. The prohibition of such conscription is directed particularly to the provision of medical services.

The idea, that constitutional provisions protect fundamental legal rights, plays a prominent role in an understanding of these express limitations and, indeed, of the implied constitutional limitations derived from them.

The “no conscription” requirement to be found in that constitutional provision amounts to an explicit limitation on mandating the provision of medical services, for example, compulsory vaccination, which remains governed by the contractual relationship between patients and doctors. Section 51(xxiiA) could thus also be regarded as an implied constitutional right of individual patients to refuse vaccinations.

The concept of “civil conscription” was first considered by the High Court in 1949 in British Medical Association v Commonwealth.6 Legislation which required that medical practitioners use a particular Commonwealth prescription form as part of a scheme to provide pharmaceutical benefits was declared invalid as a form of civil conscription. In the opinion of Latham CJ, civil conscription included not only legal compulsion to engage in particular conduct, but also the imposition of a duty to perform work in a particular way. Williams J, in his judgment, stated that “the expression invalidates all legislation which compels medical practitioners or dentists to provide any form of medical service” .

Hence, if the medical profession were directed by the Federal Government to mandatorily vaccinate people, such direction would constitute unconstitutional civil conscription. Such direction would interfere with the relationship between the doctor and the patient – a relationship which is based on contract and trust.

Of course, a doctor who freely performs his or her medical service does not create conscription. However, as Justice Webb explicitly mentioned: “When Parliament comes between patient and doctor and makes the lawful continuance of their relationship as such depend upon a condition, enforceable by fine, that the doctor shall render the patient a special service, unless that service is waived by the patient, it creates a situation that amounts to a form of civil conscription.”

Accordingly, any legislation that requires medical practitioners to prescribe government-mandated medical services, such as vaccinations, constitutes a form of civil conscription that is constitutionally invalid. Webb J’s statement also indicates that, even if the doctor were compelled to provide a service, the patient would have the right to waive that service. In other words, the Commonwealth parliament is not constitutionally authorised to force or compel any individual to accept vaccination or a medical procedure against his or her own will.

In 2009, in Wong v Commonwealth; Selim v Professional Services Review Committee, French CJ and Gummow J held that civil conscription is a “compulsion or coercion in the legal and practical sense, to carry out work or provide [medical] services”. Kirby J opined that the purpose of prohibiting civil conscription was to ensure that the relationship between medical practitioner and patient was governed by contract where that is the intention of the parties. For him the test whether civil conscription has been imposed is “whether the impugned regulation, by its details and burdens, intrudes impermissibly into the private consensual arrangements between the providers of medical and dental services and the individual recipients of such services.”

This view is also supported by the Nuremberg Code – an ethics code – relied upon during the Nazi doctors’ trials in Nuremberg. This Code has as its first principle the willingness and informed consent by the individual to receive medical treatment or to participate in an experiment. Hence, people’s refusal to be vaccinated may be based on the ground that the Covid vaccines are still experimental and their long-term effects and safety on its recipients are largely unknown. The unvaccinated, in relying on health implications for the purpose of refusing the vaccine, may thus ironically invoke the same argument used by proponents of vaccinations, who also rely on health grounds to promote the vaccine.

Importantly, the jurisprudence of the High Court indicates that the prohibition of civil conscription must be construed widely to invalidate any law requiring such conscription expressly or by practical implication. In other words, no law in Australia can impose limitations on the rights of citizens that directly or indirectly amount to a form of civil conscription.

Moreover, if unvaccinated Australians were to face serious restrictions of rights and freedoms – as suggested by medical officers and the Prime Minister – these restrictions would violate the democratic principle of equality before the law. In Leeth v Commonwealth, Deane and Toohey JJ referred to the Preamble to the Constitution to support their view that the principle of equality is embedded impliedly in the Constitution. They said that “the essential or underlying theoretical equality of all persons under the law and before the courts is and has been a fundamental and generally beneficial doctrine of the common law and a basic prescript of the administration of justice under our system of government.”

The flagged exclusion of unvaccinated Australian citizens from participation in certain activities discriminates against them on the ground of vaccine status. Of course, vaccine status is not one of the accepted grounds in any anti-discrimination legislation and, therefore, it would be possible for governments to defeat a claim that compulsory vaccination violates the equality principle. However, reliance on vaccine status would still create an apartheid-type situation since benefits would be conferred and burdens imposed on this ground. But, more importantly, the making of coercive statements to force people to get vaccinated would effectively amount to an indirect form of mandatory vaccination, the constitutionality of which is doubtful at best. Indeed, from a constitutional point of view, the jurisprudence of the High Court indicates that what cannot be done directly, cannot be achieved indirectly without violating s. 51 of the Constitution.

Additionally, compulsory vaccination adversely affects the dignity and privacy of people. Governments should be fearful of relying on the parens patriae doctrine according to which government will decide what is good for people: it would be a textbook example of the operation of the Nanny State. If governments cannot constitutionally force everyone to be vaccinated, they certainly cannot indirectly create a situation whereby everybody would be forced to take the vaccine.

This point is also addressed in a comment of Webb J in British Medical Association v Commonwealth: “If Parliament cannot lawfully do this directly by legal means it cannot lawfully do it indirectly by creating a situation, as distinct from merely taking advantage of one, in which the individual is left no real choice but compliance”.

To conclude: the Australian Constitution explicitly prohibits any form of compulsion upon the citizens to take any form of medical or pharmaceutical service, including vaccination.

On this view, unvaccinated Australians still remain decent members of society and they cannot be treated as second class citizens.

Gabriël A. Moens AM is emeritus professor of law at the University of Queensland and served as pro vice-chancellor and dean of law at Murdoch University. He is the co-author ofThe Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia Annotated (9thEd., LexisNexis, 2016).

Augusto Zimmermann is professor and head of law at Sheridan Institute of Higher Education in Perth. He is also professor of law (adjunct) at the University of Notre Dame Australia, president of the Western Australian Legal Theory Association, editor-in-chief of the Western Australian Jurist law journal, and a former law reform commissioner in Western Australia. He is the co-editor of Fundamental Rights in the Age of Covid-19, a book with contributions from leading legal academics and policymakers in the field.

TRIUSIO URVAS Kokybiškos informacijos sistemizuotas srautas, be tiesos ministerijos cenzūros

TRIUSIO URVAS Kokybiškos informacijos sistemizuotas srautas, be tiesos ministerijos cenzūros